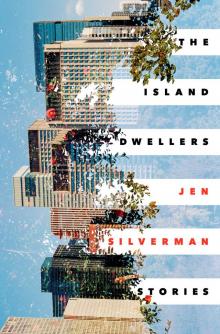

- Home

- Jen Silverman

The Island Dwellers Page 2

The Island Dwellers Read online

Page 2

Camilo frowns. He is disappointed in the smallness of our minds, “our” as in Human, as in the entire species. He is disappointed in the way we rope ourselves in with feelings of jealousy, insecurity, resentment. There is a whole landscape of human experience. Camilo doesn’t understand why we are not out there on the ridgeline of that landscape, arms spread to the wind, embracing it all. Camilo wants me to know that he is not disappointed in me specifically because he knows that I am trying as hard as I can to grapple with the limitations produced by my upbringing, but nonetheless, he wonders if this is a learning opportunity for me. Maybe, in this moment, I can push myself. I can challenge myself. I can go to Gina’s rooftop party.

I want to be better than I am.

I want to be open-minded, and spiritually free, and I don’t want to be the sort of person who is psychologically fettered in the way that (the more time I spend with Camilo and his friends) it becomes clear I am fettered.

I go to Gina’s rooftop party.

* * *

—

IT’S ON THE ROOF OF an old rectory that became a warehouse that became a ward for the mentally ill that is now a series of artist studios, or some lineage in some order. Ev comes with us. He is using male pronouns now, instead of E. There is a fine peach-fuzz starting on his upper lip. He’s embraced cut-offs and sleeveless tees, and he gives me a bro-nod when we meet on the street corner below the rectory-cum-warehouse-cum-insane-asylum. “Where the party at,” says Ev. I don’t think I’ve ever before heard him construct a sentence that starts “Where the party,” and ends with the dangling preposition “at,” but Camilo doesn’t seem to notice.

“Hey!” Gina’s voice drifts down to us. We direct our attention up to where she leans over the edge of the roof. “You guys!”

“Hey!” Camilo yells back. I can count his teeth in his grin. He is waving both hands: one is no longer enough.

“I’ll come down!” yells Gina, and she vanishes from the roof edge.

“Good times,” says Ev, who has never before used the phrase “Good times.”

Gina appears on the sidewalk. Her hair is dyed red and she’s wearing a translucent white tee and blue cut-offs. “Red white and blue!” she says, in case we didn’t make the connection.

“Oh wow,” says Camilo, who normally can’t witness nationalistic displays without discussing immigration reform, but who is now suddenly amenable. “Wow, yeah.”

Gina gives him an extra-long hug. Then she gives me an extra-long hug, for almost exactly the same number of seconds. It’s not like I was counting, but it’s also not like I wasn’t counting. She isn’t wearing a bra and she presses against me, close. “It’s so good to see you,” she says, her breath warm on my cheek.

Camilo introduces her to Ev, and they shake hands. I catch Ev staring at her tits through her T-shirt. Gina leads us up the narrow winding stairs, giving us the brief guided tour: studios down that dim hall, more studios down the next one, bathrooms on this landing, we have to climb the fire ladder to the roof, nobody’s scared of heights, right? I’m trying to figure out what it means that Gina gave me the same number-of-seconds hug that she gave Camilo. Does this mean she doesn’t want to fuck him anymore? Does it mean she wants to fuck me? Was it an apology or a come-on? If she wants to fuck me, and if I say yes, does that mean that I’m sexually liberated too?

Out on the roof, Gina’s primary and secondary partners are drinking PBR. She introduces us: Frankie is her boyfriend, but she says “primary partner,” and he’s a DJ. They’ve been together for five years. Macey is her girlfriend, but she uses the phrase “secondary partner.” They met on Tinder last week. I watch Camilo’s face. He’s impressed. Frankie shakes everybody’s hands, little tight-handed minor eruptions of a shake. Macey is sprawled out in the shade, all loose bare legs and cut-off jeans. She’s sexy as shit, and she doesn’t get up for anyone.

Gina urges us to help ourselves to PBRs and hot dogs. Frankie the DJ is running the grill, and Ev takes over helping him. They grunt to each other as they flip mighty burgers and prod engorged hot dogs, wiping sweat off their foreheads in masculine solidarity. Gina, Camilo, and I join Macey in the shade. Macey chews gum at an alarming speed. Gina tells us about the sculpture she’s working on down in her studio—it might look like a chair but it’s more than just a chair, she’s incorporating it into a dance piece about hysteria and misogyny.

“Doctors used to masturbate chicks,” Macey offers. “It used to be, like, part of their treatment. Getting fingered.”

“It did?” Camilo asks, interested.

“Macey went to Barnard,” says Gina. “She’s Canadian.”

“I dropped out,” says Macey, and elaborates no further.

Gina tells us about the other piece she’s been working on, at an artist residency in Dubai. Well, she started it there, but then continued working on it at a subsequent residency in Berlin, and now she has a residency coming up in Beijing and she hopes to finish it there. We never get to what the project is, because Ev and Frankie call us over to the grill. Camilo tells Gina over his hot dog that he’s so impressed with her drive and ambition and dedication, and that he personally is feeling lost. Gina sympathizes that it’s so important for artists to feel lost, because then you can incorporate that lost-ness into your artwork. Camilo offers that he thinks the root of his problem lies with his mother; she makes him feel incapable and resentful for days after he has had to talk to her. Gina muses that maybe Camilo should continue developing the performance piece about his mother that he’d shared when they first met, at the artist colony. Then there is a meaningful silence between them, in which they jointly recall all that they shared at the artist colony.

Frankie chomps on his burger, completely unthreatened, calm and secure because he is an Artist with Similar Values, and he doesn’t care that Gina fucked Camilo for three days in a variety of positions, some of which Frankie himself may never have imagined. Macey chews a hot dog while storing her gum in her cheek, completely unthreatened because she is as dumb as two rocks rubbing together. Ev continues to eye Gina’s tits. I find myself laid bare to the vast realization that I am three seconds away from flinging myself off the edge of the roof. In the moment, this feels less like hyperbole than fact.

Gina invites us all to come down to her studio and see her performance womb-chair. Ev and Camilo are eager, and they follow her down the fire ladder, with Frankie trailing behind. I don’t make a move and am unnerved when Macey doesn’t either. She just stretches out her long legs and moves her gum from the inside of her cheek back to the central chewing-area of her mouth. She’s done with the hot dog. The air is thick and damp with heat, and we both glisten even in the shade. Macey smells like sweat and sugar, even from a few feet away. Barnard, so: no deodorant. But Canada, so…maple syrup?

“I don’t give a shit about art,” says Macey.

“Excuse me?”

Macey tucks the gum under her tongue and enunciates, even though I heard her the first time: “Fuck. Art. Who cares? You care?”

“I don’t know,” I say.

“You an artist?”

“Not exactly.”

“Whaddayou do?”

“Theatre,” I say, like I’m confessing to a crime. “I work in the theatre.”

“That’s not art,” Macey absolves me, and for the first time I like her.

“Why’s it not art?”

“Actors and prostitutes used to be the same thing,” Macey says. “ ‘Art’ is like: What is that shit? You don’t make money.”

“You don’t usually make money from theatre either,” I say, determined to come clean.

“Broadway,” says Macey, unconcerned. “Wicked.” She spits her gum out over the edge of the roof, pops another piece in. Works at it with her tiny jaws. Offers me a piece, I take it but then don’t know what to do with it while I’m drinking PBR. “You know G

ina?”

“We’ve met,” I say. “Camilo knows her better though.”

“Yeah, they fucked.” Macey darts her eyes over me. “You and Gina?”

I don’t know if I should say no like “absolutely not,” or no like “not yet,” so in the end I just try for a very casual shake of the head accompanied by an equally blasé “huh-uh.”

Macey jerks her chin toward the exit where our compatriots vanished, implicating them in her question. “You having fun?”

I’m going to volley a bright “Yes!” and then I hear myself say, “Not really.”

“So go home. It’s Independence Day. Be fuckin’ independent.”

I don’t know what compels me toward honesty, but I say: “Camilo wants me to have a good time.”

Macey’s mouth quirks. She works the gum extra hard for a second. Then she says: “You know what I’m gonna do? I’m gonna get off this rooftop. And I’m gonna get some iced coffee. And you know what I’m not gonna think about? Motherfucking art. You wanna come?”

I stare at her. I don’t move. I am a small bird caught in the eye of a hawk. Or a spotlight. Or a storm. Macey gets up. She scratches herself right where her thigh meets her underwear.

“Yeah or no?” she asks.

“Yeah?” I say.

“Great,” says Macey the Girl Canadian. “Let’s get the fuck outta here.” And she climbs down the fire ladder. I wait five seconds, a respectful distance between a worshipper and her sudden pagan god, and then I climb after her.

* * *

—

MACEY DOESN’T HAVE ANY CHANGE and the coffee shop won’t take a credit card, so I buy Macey’s coffee. She doesn’t apologize for this. She doesn’t apologize for anything. She says, “Cool, thanks,” with genuine pleasure, like she’s scored a freebie, so I say, “You’re welcome,” and mean it—which makes me think that it’s been a long time since I’ve said, “You’re welcome,” and the person has genuinely been welcome.

We sit outside the coffee shop in the sort of heat that makes you feel like you’re living inside somebody’s mouth. I don’t expect Macey to ask me anything about myself but she asks what I’m working on. I tell her that I don’t really have anything right now.

“Bullshit,” Macey says. “I’m not saying you have to sound smart, just answer the question.”

So I tell her that I’m working on thinking about islands.

“Like. Hawaii?”

Sure, I say, or like…that TV show Lost. Like: trapped and no way out. Like: these weird moments in our lives when we look around and realize that we are in a place without a bridge or a ferry or anything. Then I explain that this is, clearly, a metaphor.

Macey says, without missing a beat, “That chubby little dude must be a crazy good lay for you to put up with so much bullshit.”

“Camilo?” I ask, amazed.

“Isn’t he?”

“Not really,” I admit.

“Then what is it? Nipples taste like beer?”

“Jesus,” I say, but I’m laughing. She keeps looking at me, waiting for me to answer. I want to say that I don’t know enough about art. I want to say that I’m not very evolved yet. I want to say that I get jealous and angry, whereas Camilo and his friends are somehow managing to leave these feelings behind in their pursuit of transcendent art-driven Zen socialism. I want to say that if we are ever to improve as humans, we must recognize all of the ways in which we are inadequate, and then put in the work to become more adequate. I want to say that the problem with a capitalist world is the devaluation of community, and that when you find a community dedicated to being the best humans they can be, the best artists they can be—well. You, who are so failed and flawed, will of course not understand why and how they do what they do. Not at first. But after you try long enough, you too might reach a place of peace and happiness and liberation.

I want to say all of these things, but every time I try to shape the sentences, I hear them all in Camilo’s voice. So in the end, I don’t say anything. And somehow, that says enough.

“Okay,” Macey says, and pats my leg. It’s such a weird old-person gesture from such a hot and brassy Canadian, that I find it comforting. “It’s okay.”

“I don’t feel okay,” I say. This is something I know how to say, in my own voice. “I don’t feel okay most of the time.”

“Yeah,” Macey says.

We sit in silence. We drink our iced coffees. Macey’s sweat-and-sugar smell has become a pungent musk that I don’t find displeasing. It occurs to me that I don’t feel the desire to be anywhere other than here. This must be what peace feels like.

“You know,” Macey says into the silence, “if you test the DNA of island dwellers, like on real isolated ones, they’re all related to each other?”

“Is that true?”

“Yeah,” says Macey. “Because who else is there to make life with? You just have to keep using each other. I mean you’re all on an island. You know?”

“I guess so,” I say, mulling the idea over.

And then Macey tells me a story.

* * *

—

BEFORE BARNARD (AND TINDER, AND GINA), Macey traveled around the world on a ship. The captain was also Canadian. He was her best friend from high school, had a trust fund but wasn’t a dick about it, and had been planning the trip ever since they were freshmen. The crew was made up of Macey, her ex-girlfriend (who Macey still occasionally slept with), and a guy named Pierre who knew a lot about boats. Macey said the trip mostly went well, all things considered. They traveled a lot and they saw a lot, and they all got along. No huge fights, no huge storms.

“But then one time things go wrong,” Macey says. I’m leaning forward by now. I’m listening to the story while also noticing how sweat gleams faintly on her upper lip, and I have a tiny animal instinct at the back of my brain to lick it off.

“This storm sweeps us off course and fucks up our boat. And we need some repairs, I won’t bore you with the details, but we’re like…in deep shit. Middle of nowhere. I mean nowhere. We’re drifting and sweating and trying to figure out what the fuck to do, and we’re taking on water, and then Pierre looks at these old maps and figures out that we’re near this island that’s half-owned by America. No idea what the deal is with the other half, but we set a course there.”

Macey takes a sip of her iced coffee and takes me in. She’s pleased with the concentrated focus of my attention, so she continues.

“We end up in eyesight of the island, and we radio, and they radio back and send a little boat out for us. And the second it pulls alongside, we see that—the guy on the boat? There’s something wrong with him. I don’t know. You can’t quite…but there’s just a little bit something wrong. His eyes and his…teeth? But he’s friendly enough, we follow him to dock—and it’s like…there are so many flies. And it’s hot. And all of the structures are a little bit broken, even in small ways, the dock has bits of wood hanging off it, every door seems to have its door handles falling off. They tell us that they can fix the boat but we’ll need to stay there overnight, and then the dude who came out for us says he knows a family that would let us stay with them, if we give them money for food.

“The second we walk into their house, we know there’s something wrong with them too. It’s like this sort of seeping wrongness that’s got itself into every crack. Their eyes don’t quite focus. The way they move is a little…bow-legged? It’s like we’ve walked into a different universe where there are different laws about the way bodies should be put together. There are three kids, and they all have these super-thick-lensed glasses, and their eyes don’t focus either. They all move in the same sideways scuttle. The three kids don’t speak. I mean, we never hear them speak. One of them at one point runs into the doorframe? She doesn’t even squeak. Just a little whoosh of breath. It’s uncanny.

�

��The wife is gigantic—big shoulders, big arms. Her husband is much skinnier. The wife is clearly not happy to see us, and she and her husband argue about it in the other room—we can’t make out words. And then the wife comes back and she’s clearly lost the argument and she makes this Okay Fine sort of noise, and she goes and takes a slab of meat off a shelf.”

Macey pauses here and lights up a cigarette. She offers it to me. I don’t really smoke, but I want to put my mouth where Macey has put her mouth. So we pass the cigarette back and forth.

“The woman starts hacking the meat into chunks with a knife. But this meat is crawling. Flies have been running over it, and giving birth to whole new generations of flies that are running over it. This meat is rancid as fuck. And we are just…wide-eyed, we don’t know what to say. Because we’re so fucking hungry. And I’m thinking: When she cooks it, will that kill all the fly eggs? Maybe she can just fry the fuck out of this shit like a strip steak.

“She finishes chopping the meat. And she sort of spoons it onto tin plates. And she puts those plates right in front of us. Dinner! And then her husband comes in. He takes a plate and he nods to us to join him and we all sit down together, and he starts eating. And we look at each other. We don’t want to be rude. We don’t want to be these rude horrible people who come in on a broken boat and judge. But also…

“My friend and I, the captain, we look at each other in the eyes like: Are we gonna do this? And then my ex-girlfriend, real soft, she goes: ‘I’m gonna be sick.’ And we’re like: ‘Don’t, don’t.’ And she’s like, ‘Guys, I’m so sorry.’ But she’s pale as a sheet. She’s not being dramatic. She’s gagging. So the captain speaks up and he says: ‘I am so sorry, we thank you so much for your hospitality, but actually none of us can eat meat. We’re all Buddhists.’ The man and his wife don’t know what Buddhists are. ‘It’s a religion of people who can’t eat meat,’ says my friend. This causes a commotion, because the wife just wasted all this great meat that she was saving that was gonna last them all week, and what are they supposed to do now! My friend the captain says: ‘We will pay you extra for this food. We can’t eat it, but we will pay you for it.’ And then he says that we’re all going to go check on our ship.

The Island Dwellers

The Island Dwellers